Dentro Fora Entre

O Caminho de Nietzsche, Serra da Arrábida, 2012

Marta Wengorovius (Abril 2014)

“Quando os homens morrem entram na história. Quando as estátuas morrem entram na arte. É a essa botânica da morte que nós chamamos cultura.” 1

“O infinito?/ Diz-lhe que entre./ Faz bem ao infinito/ estar entre gente.” 2

Prólogo

A obra de arte, tal como a filosofia, deve provocar correntes de ar, fazer entrar em nós o ar, fazer entrar o infinito.

Desde 2005 que encontro em mim, no meu trabalho, uma pré-disposição, ou mesmo um encantamento, pelo rebatimento da parede do museu para a rua, para a cidade ou para a natureza. Por vezes, como no caso dos Objectos de Errância (2005-2012) 3, isto significa a possibilidade de pegar nas obras e sair para fora – usá-las e voltar para as guardar, tanto na sua caixa como no museu. Entre 2005 e 2012, os Objectos de Errância foram ‘usados’ com encontros marcados. Estes encontros eram mais ou menos complexos, conforme as situações. Por exemplo: quando me convidaram para participar numa exposição no Centro Cultural de Cascais, organizada pela Quinta Essência (uma associação que trabalha com pessoas autistas), encontrei-me num jardim com uma das adolescentes com quem dessa associação, para que ela usasse duas obras que eu tinha a acabado de produzir: Olho #1 e Olho #2 (arco-íris). A exposição foi aquele momento no jardim – o uso dos objectos, o intervalo de tempo reservado para tal – e o jardim foi o museu. Algumas performances mais complexas relacionadas com os Objectos de errância exigiram o estudo do local, desenhos e plantas de actuação, ou até o estudo de quando seria o ocaso ou o nascer do sol em determinados dias. Algumas acções aconteceram na serra, outras na praia, fora ou dentro do museu. A imagem da parede rebatida do museu significa também a ligação possível com a cidade, com a universidade, com o jardim, uma comunicação que abre a ‘caixa-arquitectura’ do museu ou que a fecha, conforme o que a obra exigir. No museu, as obras de arte nele tornam-se obras abertas a um outro, a um desconhecido e no caso dos Objectos de errância, onde as obras podem ser requisitadas para uso, este factor é importante. Dentro, fora, entre: o museu e o quotidiano como espaços em diálogo fluido, tirando partido das suas potencialidades. Talvez aí “as estátuas não tenham que morrer”. Utopia?

Escreveu Michel Foucault:

“A história será efectiva na medida em que introduza o descontínuo no nosso próprio ser. Dividirá os nossos sentimentos; dramatizará os nossos instintos; multiplicará o nosso corpo e opô-lo-á a si mesmo. (…) O saber não foi feito para compreender, foi feito para fazer cortes.” 4

Primeiro corte: Universidade

Estamos na Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas da Universidade Nova de Lisboa, a 2 de Dezembro de 2010. Dentro do pequeno auditório da Universidade defende-se uma tese de Doutoramento em Filosofia sobre Nietzsche. O título da tese é Arte e filosofia no pensamento de Nietzsche, a candidata é Maria João Mayer Branco. Oiço e absorvo com atenção todas as palavras, mas uma ideia inquieta-me (ou torna-me inquieta?): o que seria aquele texto dito noutro contexto? Como transpor este discurso para uma montanha? Como torná-lo uma experiência? Penso sobre o que é o conhecimento – o que é compreender – fazer entrar ar, fazer entrar infinito. Penso como se visita e pratica o pensamento de outrem. Como se entra e como se sai. E o que se traz. E como o que fica connosco, por vezes, acaba por ficar para sempre. Uma frase, um pensamento, uma ideia.

“Permanecer sentado o menos possível; não acreditar em nenhum pensamento que não tenha nascido ao ar livre e durante o movimento livre – em nenhum pensamento no qual os músculos não tenham também participado da festa. Todos os preconceitos vêm das vísceras… Ser rabo-de-chumbo, já o disse uma vez, é que é o verdadeiro pecado contra o espírito.” 5

Se, como afirma Nietzsche, os melhores pensamentos nascem ao ar livre e durante o movimento do caminhar, não deveríamos seguir esse conselho? O que acontecerá se a recepção do pensamento implicar uma mudança do sítio onde nos encontramos — como se o filósofo ainda nos esperasse na montanha… O que implica o corpo “entendido enquanto dimensão física/mental/subtil” 6, e a sua localização no espaço, no discurso, na aprendizagem? 7 Caminhar.

Penso na relação entre a recepção da palavra e a localização do corpo no espaço.

Penso em imobilidade e mobilidade. Sinto a cadeira. 8

Segundo corte: no atelier

Depois dessa defesa de tese, num primeiro encontro no meu atelier, faço à Maria João a proposta de pegarmos no tema nietzschiano A grande saúde, porque com ele vêm as questões da alimentação, da vivência, do espaço, do tempo, da descontinuidade, do corpo, da convalescença, da pausa, da marcha, do intervalo, da liberdade… Começamos então a trabalhar desenrolando este fio. Trabalhar A grande saúde era uma intuição: queria pegar no pensamento de Nietzsche sob um ponto de vista pouco habitual, que escapasse aos mais comuns e possibilitasse pensar ‘o alimento’ num terreno vasto, interesse que já vinha de trabalhos anteriores (Uso da Toalha, projecto iniciado em 2005). A de 4 abril de 2011, a Maria João escreveu-me:

“Envio-te umas palavras de Nietzsche para dar continuação ao nosso projecto: ‘Sou demasiado curioso, demasiado problemático, demasiado atrevido para me contentar com uma resposta grosseira. E Deus é uma resposta grosseira, uma indelicadeza para connosco, pensadores. No fundo, até é simplesmente uma grosseira proibição que se nos impõe: não deveis pensar!… De maneira bem diferente me interessa uma outra questão, da qual depende, mais do que de qualquer curiosidade teológica, a ‘salvação da humanidade’: a questão da nutrição. Para uso diário, podemos formulá-la assim: Como te hás-de alimentar, precisamente no teu caso, para chegares ao máximo de energia, de virtù ao estilo renascentista, de virtude isenta de moralina?’ Para as ‘considerações nutricionais’ de Nietzsche, sugiro-te que leias as primeiras páginas do capítulo Por que sou tão perspicaz do Ecce Homo. Uma achega: para beber, água, nada de álcool, e chá só de manhã.”

Para as “considerações nutricionais” de Nietzsche, sugiro-te que leias as primeiras páginas do capítulo “Por que sou tão perspicaz” do Ecce Homo. Uma achega: para beber, água, nada de álcool, e chá só de manhã.” (4 abril 2011).

Terceiro corte: a exposição e a serra

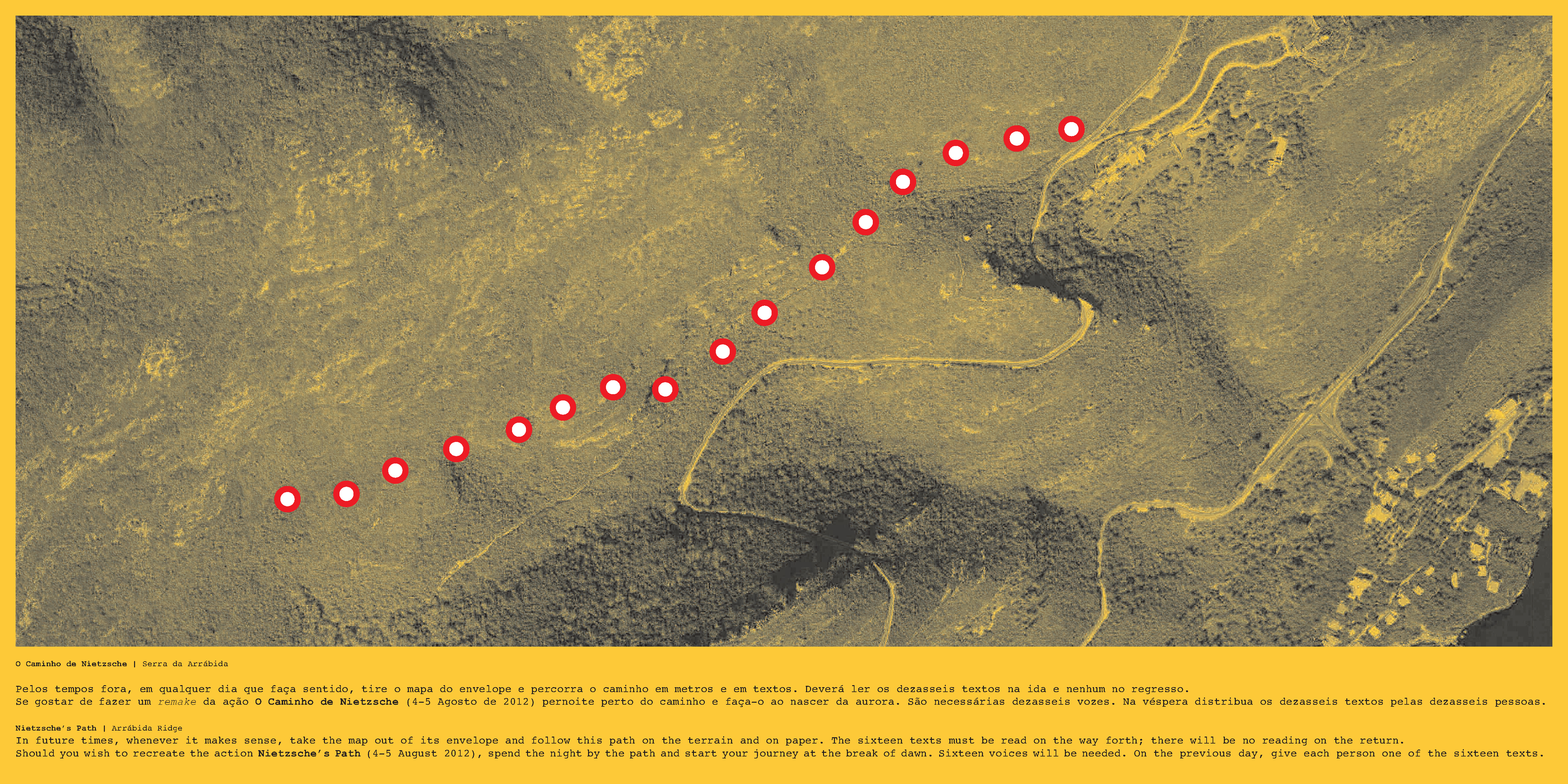

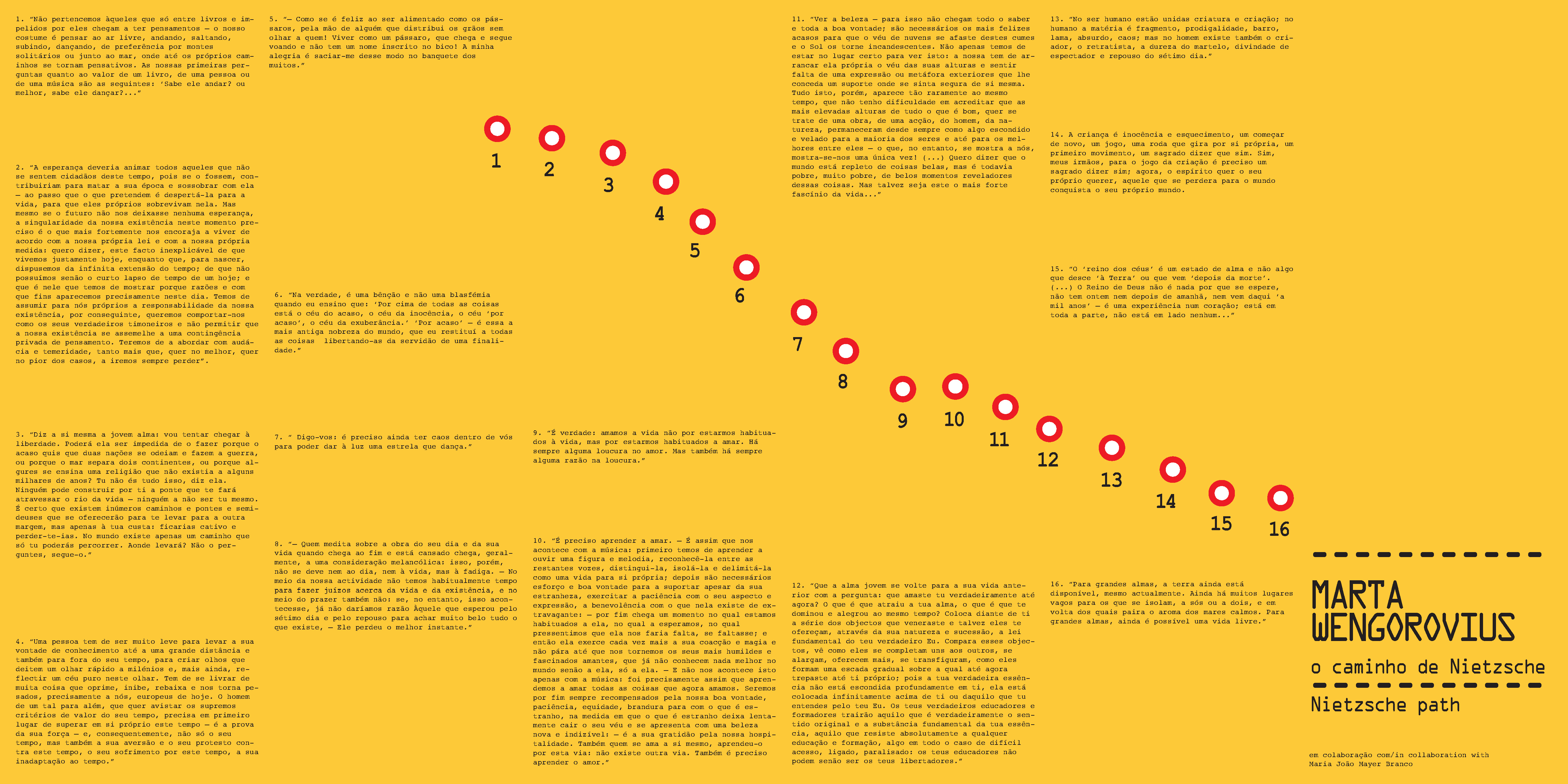

A pouco e pouco, o conceito da exposição A grande Saúde foi-se definindo: a exposição seria constituída com uma parte ‘dentro’ do espaço (Sala do cinzeiro, Fundação EDP) e a montanha : a parede rebatida do museu de que falo no início do texto. Assim, com a fluidez entre o museu e a serra, entre o dentro e o fora, surgiramu o filme O caminho de Nietzsche (dezasseis vozes), que traria o percurso e o texto para dentro do espaço, e o mapa O caminho Nietzsche, que levaria para fora, para a montanha, a obra.

“Não pertencemos àqueles que só entre livros e impelidos por eles chegam a ter pensamentos — o nosso costume é pensar ao ar livre, andando, saltando, subindo, dançando, de preferência por montes solitários ou junto ao mar, onde até os próprios caminhos se tornam pensativos. As nossas primeiras perguntas quanto ao valor de um livro, de uma pessoa ou de uma música são as seguintes: ‘Sabe ele andar? Ou melhor, sabe ele dançar?…” 9

Comecei a passar temporadas, intercaladas por visitas da Maria João, perto da serra da Arrábida 10, perto da terra, para poder iniciar a ligação entre os alimentos e os primeiros desenhos (porque foi pelo alimento que comecei a série de desenhos); e iniciei as caminhadas na serra para procurar que lugares e que perspectivas queria tomar para a realização do filme O Caminho de Nietzsche – dezasseis vozes, assim como os percursos de reconhecimento para “desenhar” o caminho onde se daria a acção com a leitura, na serra, dos dezasseis textos. A serra é uma reserva natural com áreas protegidas e não foi fácil encontrar um caminho autorizado. Queria descobrir o trajecto e uma forma de o levar para dentro da exposição. Há muito que a ideia de movimento estava no meu trabalho. O passo. Caminhar. E assim surgiu a projecção do mapa: como num mapa de viagem, agradava-me a ideia de despoletar um caminho, um acontecimento, mas de seguida poder guarda-lo sem que nenhum registo físico ficasse na montanha. Agradava-me também que este ‘desenho’ efémero, pelo facto de passar a existir um mapa, pudesse ser sempre, ao longo dos tempos, re-feito. Utopia?

Inventar sobre a terra conhecida — a cartografia do mundo está finalizada – desenhemos por cima. Assim, inspirado na ideia de caminhar e de ligar esse caminhar ao pensamento, desenhou-se um percurso na serra pontuado por dezasseis leituras de textos escolhidos de Nietzsche, e editou-se um mapa com os textos e as instruções.

O mapa também pode ser visto como ‘corte’ ou desvio no espaço e no tempo um desenhar sobrevoando o terreno e o tempo — tanto passado, como presente, como futuro. Corte ou ligação, o passo e o texto entre a terra e o céu. Se a terra traz o caminho, o movimento do corpo traz o pensamento: acção des-contínua – suspensão – tempo.

As instruções inscritas no mapa:

“O Caminho de Nietzsche (Serra da Arrábida)

Pelos tempos fora, em qualquer dia que faça sentido, tire o mapa do envelope e percorra o caminho em metros e em textos. Deverá ler os dezasseis textos na ida e nenhum no regresso. Querendo fazer a ação O Caminho de Nietzsche, pernoite perto do deste caminho e faça-o ao nascer da aurora. São necessárias dezasseis vozes. Na véspera distribua os dezasseis textos pelas dezasseis pessoas.”

As instruções estão ‘desenhadas’ para que haja futuro. Mas pode ser uma utopia, pois como tomar conta do infinito que as obras performativas contêm? Basta provocá-lo deixando para isso instruções, documentos, filme? Fotografias? Vozes gravadas?

Começou a tornar-se mais claro que a acção O caminho de Nietzsche pedia um afastamento maior e um contexto concreto. Assim, surgiu a ideia de pernoitar no convento da Arrábida. Estar um tempo no convento também alteraria a forma como se ‘vê’ / ou como se “vive” uma obra. Isto é, quando se ‘vê’ uma exposição ou uma performance num museu ou galeria há um tempo certo para ‘ver’; na acção o Caminho de Nietzsche foi possível aliar e fazer dialogar o tempo para ensair e actuar, com o tempo para viver (dormir, acordar, alimentar – descobrir onde ali nasce ou se põe o sol; a apropriação do lugar). Aquilo que é comum na vivência de um lugar como contexto para criação do ‘menos comum’ – a arte?

Quarto ‘corte’: a propósito das vozes – filme e caminho

O que é ensaiar? Qualquer pessoa pode tirar partido desta experiência: ensaiar, neste caso experimentar dar voz a um pensamento, a um texto. E podemos ver o ensaio aqui de novo como ‘cortar’, sair de nós próprios, sair de um quotidiano. Mais ainda, integrar este gesto criativo num quotidiano. De novo fazer entrar o ar? Fazer entrar o infinito? Todos deveríamos ter espaço para o ensaio, o ensaio de um-eu, um ensaio de um – nós; experimentar a nossa voz, conhecê-la (voz/quotidiano/voz/ensaio). A presença da voz como o que está ‘entre’ dentro do corpo — a voz como o que traz para fora e dá uma forma de uma enorme presença com a sua qualidade presencial e efémera — quando acabamos de dizer já dissemos. A voz é o que mais transporta a nossa identidade, o mistério de sermos únicos. Escolhi então as dezasseis vozes para o filme.

Algumas dessas vozes seriam as mesmas que fariam a leitura de textos na performance na serra. Tinham aberto as inscrições para a acção O caminho de Nietzsche e começava-se a desenhar o grupo (Junho 2012).

Quinto corte: O Caminho de Nietzsche, serra da Arrábida, 5 de Agosto 2012

Sabíamos o percurso: na repérage tínhamos decidido até onde iríamos, tínhamos descoberto uma clareira onde chegar.

“No dia a seguir acordámos cedo para tomar um café rápido e umas sandes de pepino em quadradinhos. Não podíamos perder a aurora e iniciámos a caminhada. Alguém pergunta: ‘estamos todos?’ e a Marta responde: ‘Todos? Todos é uma utopia.” 11

Saímos do convento por volta das 6h30m. E continuámos, de certa forma, o ensaio. A única coisa ‘coreografada’ era a escolha do caminho e a decisão de que os textos eram lidos durante a ida e nenhum na volta. Tinha-se decidido na véspera quais as dezasseis vozes que leriam os textos durante o caminho (algumas eram as das mesmas pessoas que gravaram o texto para o filme). Fomos subindo lentamente a montanha e fazendo as dezasseis paragens, dizendo as dezasseis leituras, ouvindo as dezasseis vozes.

Quando chegámos à clareira final, apercebi-me de que não tinha pensado como ‘saiarímos’ dali, isto é, qual o tempo de permanência no lugar, qual o tempo de silêncio e qual o sinal para ‘desfazer’ a obra.

E foi então que, olhando para cada pessoa, tive uma epifania: vi cada um dos participantes como uma ‘escultura viva’. E percebi que essa era a ‘obra’. E que ela acabara de acontecer.

1 Texto de Chris Marker para o filme As estátuas também morrem, Alain Resnais e Chris Marker, 1953.

2 Verso de Alexandre O’Neill.

3 Objectos de Errância, obras que elaborei para a dissertação de mestrado O evento como pintura. Mestrado Artes Visuais e Intermédia, Universidade de Évora, 2007.

4 Michel Foucault, Nietzsche, la généalogie, l’histoire, 1971.

5 Nietzsche, Ecce Homo, 1888

6 Alberto Carneiro, texto O subtil na criação: o método não método: “Corpo entendido na sua unidade/identidade/diversidade, enquanto dimensão física/mental/subtil, pela qual o que se torna consciente vai formando um conjunto de relações emergentes de sensações onde todos os órgãos sensoriais se conjugam na construção de imagens plásticas”.

7 Uma imagem acompanha este meu pensamento: uma aula de Joseph Albers (Josef Albers teaching at Yale by John Cohen, ca. 1955): ele está de pé e percorre o espaço ensinando com um círculo na mão. Os alunos estão de roda, também de pé e andam no espaço para onde este os dirige, ouvem-no, e a aula dá-se numa espécie de movimento contínuo. Para Albers, o objetivo das suas aulas era ensinar a ‘ver melhor, ensinar a ‘abrir os olhos’. Acreditava na ligação da observação directa e na descoberta pessoal.

8 E outra imagem vem-me ao pensamento: vestígios de experiências pedagógicas do Jardins de Infância (de 1966 a 1975) projectados e dirigidos pela minha mãe. O espaço, uma casa enorme com um jardim muito grande, uma casa como que abandonada, vazia, onde a escola ocupava um espaço emprestado e um pouco de terreno onde plantávamos. A imagem, para além de outras, que importa aqui agora somos nós, alunos, crianças, sentados no chão, numa roda, no centro está um aquário com um peixe, vamos observando o seu movimento, estamos a “estudar” o peixe. Primeiro eram-nos apresentadas ‘as coisas”, a realidade (observação); depois vinha a descrição verbal dos conhecimentos que adquiríamos da observação (associação) e por fim o desenho ou as palavras escritas (expressão). Assim apareciam no meio do espaço da aula galinhas, coelhos, peixes… por vezes improvisavam-se redes para manter o animal dentro da sala e muitas vezes, depois da acção, estes ficavam a viver na escola. Este método advinha das experiências pedagógicas propostas por Decroly, que seguem do concreto para o abstracto, através aquilo a que Decroly chamava os centros de interesse. Este desenvolveu uma pedagogia que fazia uso da globalização por acreditar tratar-se de um caminho natural para apreender o conhecimento. O seu método questionou a divisão das disciplinas pois considerava que isso não permitia o conhecimento da realidade viva (total).Dizia que o ensino fragmentado não favorecia o desenvolvimento da inteligência, porque reduzia a aprendizagem a uma transmissão isolada, o que por vezes podia até levar a criança a desinteressar-se pela escola. Penso hoje o quanto é importante revesitar estes assuntos.

9 Texto N1 do Mapa O Caminho de Nietzsche (textos escolhidos pela Maria João para o projecto do caminho).

10 Elaboração dos desenhos que constituiriam a exposição sobre o tema a Grande Saúde, Fundação EDP, onde também seria exposto o mapa: O Caminho de Nietzsche e o filme O Caminho de Nietzsche – dezasseis vozes, 2012.

11 Tirado do texto “Relato sobre evento no Convento da Arrábida (parte 1)”, Maria Lusitano Santos.

Inside Outside Between

O Caminho de Nietzsche, Serra da Arrábida, 2012

Marta Wengorovius (April 2014)

“When men die, they enter history. When statues die, they enter art. This botany of death is what we call culture.” 1

“The infinite?/ Tell him to come in./ It’s good for infinity/ to be among human company.” 2

Prologue

A work of art, like philosophy, should stir up currents of air. It should inspire us, bring in the infinite.

Since 2005, I’ve discovered, in myself and in my work, a predisposition towards, or even a fascination with, the transposition of a museum’s walls into the street, into the city and into nature. Sometimes, as in the case of Objectos de Errância (2005-2012) 3, this signifies the possibility of taking the works outside – using them and then returning them to be kept in their boxes or in the museum. From 2005 to 2012, these Objectos de Errância were ‘used’ for staged encounters. These encounters were more complex or less complex depending on each situation. For example: when I was invited to participate in an exhibition at the Centro Cultural de Cascais, organised by Quinta Essência (an association that works with autistic people), I found myself in a garden with a teenager from the association, who was to make use of two works that I had just finished creating: Olho #1 and Olho #2 (arco-íris). The exhibition was that very moment that took place in the garden – the use of the objects, the time allotted for the exhibition – and the garden was the museum. Some of the more complex performances of Objectos de errância required me to study locations, produce drawings and draw up action plans, or figure out when the sunset or sunrise would occur on specific days. Some events took place in the mountains, others at a beach, outside or inside the museum. The image of a museum’s walls transposed to some other place also signifies a possible connection with the city, with the university, with the garden – a communication that opens the museum’s ‘architecture-box’ or closes it, depending on the requirements of the work. In the museum, the works of art become works that open to the other, to the unknown; in the case of Objectos de errância, where they might be requisitioned for use, this is an important factor. Inside, outside, between: the museum and the everyday as spaces in fluid dialogue, making the most of their potentialities. Perhaps “statues need not die” there. Is this utopian?

Michel Foucault wrote:

“History becomes “effective” to the degree that it introduces discontinuity into our very being – as it divides our emotions, dramatizes our instincts, multiplies our body and sets it against itself. […] Knowledge is not made for understanding; it is made for cutting.” 4

First cut: University

We are at the Faculty of Social and Human Sciences at Universidade Nova de Lisboa on 2 December 2010. Inside the university’s small auditorium, a PhD thesis on Nietzsche is being defended. The title of the thesis is Art and Philosophy in Nietzsche’s Thinking and the candidate is Maria João Mayer Branco. While I listen attentively and take in all of her words, an idea stirs in me (or does it stir me up?): what would this text be like if it were read in another context? How would one transpose this discourse onto a mountain? How would it be turned into an experience? I think about what knowledge is – what does it mean to understand? – to inspire, to bring in the infinite. I think about how one might visit and enter other people’s thoughts. How one enters and exits. What it brings. And how what stays with us sometimes ends up staying for good. A phrase, a thought, an idea.

“Remain seated as little as possible, put no trust in any thought that is not born in the open, to the accompaniment of free bodily motion – nor in one in which even the muscles do not celebrate a feast. All prejudices take their origin in the intestines. A sedentary life, as I have already said elsewhere, is the real sin against the Holy Spirit.” 5

If, as Nietzsche asserts, the best thoughts emerge outdoors and while one is walking, should we not heed this advice? What would happen if the reception of a thought meant changing the location in which we found ourselves – as if the philosopher were still waiting for us on the mountain… What would it mean to have the body “understood as a physical/mental/subtle dimension” 6 , and to be located in space, in discourse, in learning? 7 In a word: walking.

I think of the relationship between the reception of a word and the location of a body in a space.

I think of immobility and mobility. I feel the chair. 8

Second cut: in the studio

After the thesis defence, I had my first meeting with Maria João in my studio, where I suggested to her the idea of adopting Nietzsche’s The Great Health, since it brought up questions of diet, existence, space, time, discontinuity, the body, convalescence, pausing, walking, the interval, freedom…

We thus set to work to unravel this thread. Working on The Great Health was something intuitive: I wanted to use Nietzsche’s thinking from an unusual perspective that escaped most people’s awareness, allowing one to think of ‘food’ within a vast terrain, an interest of mine that had already been present in previous work (Uso da Toalha [Use of the Tablecloth], a project that began in 2005). On 4 April 2011, Maria João wrote to me:

“I’m sending you some words by Nietzsche to continue further with our project: ‘I’m too inquisitive, too incredulous, too high spirited, to be satisfied with such a palpably clumsy solution of things. God is a too palpably clumsy solution of things; a solution which shows a lack of delicacy towards us thinkers – at bottom, He is really no more than a coarse and rude prohibition of us: ye shall not think!… I am much more interested in another question: a question upon which the ‘salvation of humanity’ depends to a far greater degree than it does upon any piece of theological curiosity: I refer to nutrition. For ordinary purposes, it may be formulated as follows: how precisely must though feed thyself in order to attain to thy maximum of power, or virtù in the Renaissance style, of virtue free from moralic acid?’9 On Nietzsche’s “nutritional considerations”, I suggest you read the opening pages of the chapter “Why I am so Clever” in Ecce Homo. Another thing: drink water, no alcohol. And tea only in the morning.” (4 April 2011).

Third cut: the exhibition and the hills

Bit by bit, the concept of the exhibition A grande Saúde was defined: the exhibition would be comprised of a part that was ‘inside’ a space (Sala do cinzeiro, Fundação EDP) and one that was on in the hills: the transposed wall of the museum that I mentioned at the beginning of this text. What emerged, then, in the fluidity between museum and mountain, between inside and outside, was the film O caminho de Nietzsche (dezasseis vozes) [Nietzsche’s Way (16 voices)], which would bring the trail and the text into the space, and a map, O caminho Nietzsche, which would take the work outside to the hills.

“We are not among those who have ideas only between books, stimulated by books – our habit is to think outdoors, walking, jumping, climbing, dancing, preferably on lonely mountains or right by the sea where even the paths become thoughtful. Our first question about the value of a book, a person, or a piece of music is: ‘Can they walk?’ Even more, ‘Can they dance?’” 10

I began to spend time near the Serra da Arrábida , close to the land, interspersed with visits from Maria João, so I could begin making a link between food and the first drawings (it was through food that I began the series of drawings). I also began to take walks in the hills to find the locations and perspectives I wanted for the film O Caminho de Nietzsche – dezasseis vozes, and to scout for the routes that would “draw” the trail, where the activity and the readings of the 16 texts would take place. The serra is in a nature reserve with protected areas and it was not easy to find an authorised trail. I wanted to find a path and a way to bring it into the exhibition. The idea of movement had been in my work for quite some time. The step. And walking. This is how the projection of the map emerged: as in a travel map, I liked the idea of blazing a trail, creating an event, but one that could later be recorded without leaving any physical trace on the mountain. What I also liked was that this ephemeral ‘drawing’, the fact that it existed on a map, could always be redone over time. Is this utopian? To invent atop a land that is familiar – the world having already been mapped – we draw over it. Inspired by the idea of walking and of connecting the walking with thinking, a trail was created in the hills, marked by 16 readings of selected texts by Nietzsche, and a map was produced, containing texts and instructions. The map can also be regarded as a ‘cut’ or a diversion in space and time, a drawing that floats above the land and time – as much in the past as it is in the present and the future. A cutting or a connection, a step and a text between the land and the sky. If the land provides the trail, the movement of the body provides the thought: dis-continuous action – suspension – time.

The written instructions on the map:

“O Caminho de Nietzsche (Serra da Arrábida). At any time, on any day that seems appropriate, remove the map from the envelope and follow the trail by metres and texts. You should read the 16 texts on the way there; do not read any of them on the way back. If you want to perform O Caminho de Nietzsche, spend the night somewhere close to the trail and set out at dawn. You need 16 voices. On the evening before you set out, distribute the 16 texts to 16 people.” 11

The instructions are ‘drawn’ so as to have a future. Perhaps this is utopian, for how does one grasp the infinite that exists in performative works? Is it enough to instigate it by leaving instructions, documents, a film? Photographs? Recorded voices? It became clear that the performance of O caminho de Nietzsche required greater seclusion and a concrete context. Out of this came the idea of spending a night at the Arrábida Convent. Spending time in the convent would also change how one ‘saw’ or ‘experienced’ a work of art. In other words, when one sees an exhibition or watches a performance at a museum or gallery, there is a specific time allotted for ‘viewing’; on Nietzsche’s Way, one could combine the time spent on rehearsing and performing with the time spent on living (sleeping, waking up, eating – discovering where the sun rises and sets; getting acquainted with the place) and create a dialogue between them. To take what is ordinary in the experience of a place as a context for creating something ‘not so ordinary’ – could that be art?

Fourth ‘cut’: about the voices – the film and the trail

What does it mean to rehearse? Anyone can benefit from this experience: to rehearse, in this case, is to try to give voice to a thought, to a text. Once again, we might view the rehearsal here as a ‘cut’, to step out of ourselves, to remove ourselves from the everyday. And more: to include this creative gesture in the everyday. Perhaps it’s to inspire, to bring in the air? To bring in the infinite? All of us should have a space to rehearse in, a rehearsal for the ‘I’, a rehearsal for the ‘We’; to experiment with our voice and to get to know it (voice/everyday/voice/rehearsal). The presence of the voice as something that is ‘in between’, inside the body – the voice as something that is transposed to the outside and gives shape to an enormous presence with its ephemeral and present quality – when we have just finished saying something, when we have already said it. The voice is what best transports our identity, the mystery of our uniqueness. I then proceeded to select the 16 voices for the film.

Some of these voices would be the same voices that would read the texts in the performance in the hills. I held auditions for the performance of O caminho de Nietzsche and began to assemble the group (June 2012).

Fifth cut: O caminho de Nietzsche, Serra da Arrábida, 5 August 2012

We knew the route: during the location scouting, we had decided where we would walk and we had found a clearing where we would end up.

“The next day, we woke up early and ate a quick breakfast and several cucumber sandwiches that had been cut up into squares. We couldn’t miss the sunrise so we began the walk. Someone asked: ‘is everyone here?’ and Marta replied: ‘Everyone? Everyone would be a utopia.” 12

We left the convent around 6:30 AM, continuing the rehearsal, in a sense. The only thing that was ‘choreographed’ was the path that had been selected and the decision to read the texts on the way up and not to read any on the way back. It had been decided the night before which of the 16 voices would read the texts along the trail (some were the same people who recorded the readings for the film). Slowly, we ascended the mountain, stopping in 16 places, performing the 16 readings and listening to the 16 voices. When we arrived at the final clearing, it occurred to me that I had not given any thought as to how we would ‘leave’ the place; that is, how long we would stay there, how long the silence would go on for and what the signal would be for ‘ending’ the work.

It was at that moment, as I looked at each person, that I had an epiphany: I saw each participant as a ‘living sculpture’. And I realised that this was the ‘work’. And that it had just happened.

1 Text from the film Statues Also Die (Les Statues Meurent Aussi), Alain Resnais and Chris Marker, 1953. Retrieved from: http://www.walkerart.org/calendar/2014/censorship-colonial-france-returning-gaze

2 Poem by Alexandre O’Neill [transl. Richard Zenith, 1997], Poetry International Rotterdam. Retrieved from: http://www.poetryinternationalweb.net/pi/site/poem/item/4720/auto/PORTUGAL

3 Objectos de Errância were works created for my Master’s dissertation entitled O evento como pintura. Master’s in Visual Arts and Intermedia, Universidade de Évora, 2007.

4 Michel Foucault, Nietzsche, genealogy, history, pp. 124 in The Postmodern History Reader, ed. Keith Jenkins, Routledge, London and New York, 1997.

5 Nietzsche, Ecce Homo, 1888 [translated by Anthony M. Ludovici, 1911]

6 Alberto Carneiro, text from O subtil na criação: o método não método: “The body is understood in its unity/identity/diversity as a physical/mental/subtle dimension, so that what becomes conscious forms a series of emerging relations of sensations in which all of the sensorial organs come together to build artistic images” (direct translation from the Portuguese version).

7 An image accompanies this thought: a lesson taught by Joseph Albers (Josef Albers teaching at Yale by John Cohen, ca. 1955): he is standing and he walks around the space as he teaches, holding a circle in his hand. The students stand around him in a circle and they walk in the space where he tells them to walk; they listen to him and the class becomes a kind of continuous movement. For Albers, the goal of his lessons was to teach people how to ‘see better’, to teach them to ‘open their eyes’. He believed in the connection between direct observation and personal discovery.

8 Another image comes to mind: memories of pedagogical experiments in kindergarten (from 1966 to 1975), conceived and directed by my mother. The space was an enormous house with a very large garden, a house that was sort of abandoned, empty, where the school was using a borrowed space and a small plot where we planted things. Among other images, the one that is important here is of us – students, children – sitting on the floor in a circle. In the middle is an aquarium with a fish; we’re observing its movements, we’re “studying” the fish. First, we were presented with ‘things’, reality (observation); later came a verbal description of the knowledge we would acquire from observation (association) and finally, a drawing or written words (expression). Chickens, rabbits and fish would appear in the middle of the classroom space… sometimes improvised wire netting was created to keep the animals inside the room and often, they would end up living in the school. This method was based on Decroly’s pedagogical experiments, which proceeded from the concrete to the abstract through what he called centres of interest. He developed a pedagogy that employed the idea of globalisation, as he believed it was a natural path for attaining knowledge. His method questioned the separation of the disciplines, as he thought that this would not allow for an understanding of lived reality (totality). He argued that a fragmented education did not encourage the development of intelligence, since it reduced learning to an isolated transmission, one that could even lead a child to lose interest in school. I think it is so important nowadays to revisit these issues.

9 Friedrich Nietzsche, Ecce Homo, [transl. Anthony M. Ludovici], p. 29, Dover, New York, 2004

10 Friedrich Nietzsche, The gay science: with a prelude in German rhymes and an appendix of songs, [transl. Josefine Nauckhoff], p. 230, Cambridge University Press, NY, 2001, Text N1 from the Map O Caminho de Nietzsche (texts selected by Maria João for the trail).

11 Preparing the drawings that would comprise the exhibition based on the theme The Great Health, Fundação EDP, where mapa: O Caminho de Nietzsche and the film O Caminho de Nietzsche – dezasseis vozes, 2012 would also be presented.

12 Excerpted from the text “Relato sobre evento no Convento da Arrábida (parte 1)”, Maria Lusitano Santos.

- + PT

-

Dentro Fora Entre

O Caminho de Nietzsche, Serra da Arrábida, 2012

Marta Wengorovius (Abril 2014)“Quando os homens morrem entram na história. Quando as estátuas morrem entram na arte. É a essa botânica da morte que nós chamamos cultura.” 1

“O infinito?/ Diz-lhe que entre./ Faz bem ao infinito/ estar entre gente.” 2

Prólogo

A obra de arte, tal como a filosofia, deve provocar correntes de ar, fazer entrar em nós o ar, fazer entrar o infinito.

Desde 2005 que encontro em mim, no meu trabalho, uma pré-disposição, ou mesmo um encantamento, pelo rebatimento da parede do museu para a rua, para a cidade ou para a natureza. Por vezes, como no caso dos Objectos de Errância (2005-2012) 3, isto significa a possibilidade de pegar nas obras e sair para fora – usá-las e voltar para as guardar, tanto na sua caixa como no museu. Entre 2005 e 2012, os Objectos de Errância foram ‘usados’ com encontros marcados. Estes encontros eram mais ou menos complexos, conforme as situações. Por exemplo: quando me convidaram para participar numa exposição no Centro Cultural de Cascais, organizada pela Quinta Essência (uma associação que trabalha com pessoas autistas), encontrei-me num jardim com uma das adolescentes com quem dessa associação, para que ela usasse duas obras que eu tinha a acabado de produzir: Olho #1 e Olho #2 (arco-íris). A exposição foi aquele momento no jardim – o uso dos objectos, o intervalo de tempo reservado para tal – e o jardim foi o museu. Algumas performances mais complexas relacionadas com os Objectos de errância exigiram o estudo do local, desenhos e plantas de actuação, ou até o estudo de quando seria o ocaso ou o nascer do sol em determinados dias. Algumas acções aconteceram na serra, outras na praia, fora ou dentro do museu. A imagem da parede rebatida do museu significa também a ligação possível com a cidade, com a universidade, com o jardim, uma comunicação que abre a ‘caixa-arquitectura’ do museu ou que a fecha, conforme o que a obra exigir. No museu, as obras de arte nele tornam-se obras abertas a um outro, a um desconhecido e no caso dos Objectos de errância, onde as obras podem ser requisitadas para uso, este factor é importante. Dentro, fora, entre: o museu e o quotidiano como espaços em diálogo fluido, tirando partido das suas potencialidades. Talvez aí “as estátuas não tenham que morrer”. Utopia?

Escreveu Michel Foucault:

“A história será efectiva na medida em que introduza o descontínuo no nosso próprio ser. Dividirá os nossos sentimentos; dramatizará os nossos instintos; multiplicará o nosso corpo e opô-lo-á a si mesmo. (…) O saber não foi feito para compreender, foi feito para fazer cortes.” 4Primeiro corte: Universidade

Estamos na Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas da Universidade Nova de Lisboa, a 2 de Dezembro de 2010. Dentro do pequeno auditório da Universidade defende-se uma tese de Doutoramento em Filosofia sobre Nietzsche. O título da tese é Arte e filosofia no pensamento de Nietzsche, a candidata é Maria João Mayer Branco. Oiço e absorvo com atenção todas as palavras, mas uma ideia inquieta-me (ou torna-me inquieta?): o que seria aquele texto dito noutro contexto? Como transpor este discurso para uma montanha? Como torná-lo uma experiência? Penso sobre o que é o conhecimento – o que é compreender – fazer entrar ar, fazer entrar infinito. Penso como se visita e pratica o pensamento de outrem. Como se entra e como se sai. E o que se traz. E como o que fica connosco, por vezes, acaba por ficar para sempre. Uma frase, um pensamento, uma ideia.

“Permanecer sentado o menos possível; não acreditar em nenhum pensamento que não tenha nascido ao ar livre e durante o movimento livre – em nenhum pensamento no qual os músculos não tenham também participado da festa. Todos os preconceitos vêm das vísceras… Ser rabo-de-chumbo, já o disse uma vez, é que é o verdadeiro pecado contra o espírito.” 5

Se, como afirma Nietzsche, os melhores pensamentos nascem ao ar livre e durante o movimento do caminhar, não deveríamos seguir esse conselho? O que acontecerá se a recepção do pensamento implicar uma mudança do sítio onde nos encontramos — como se o filósofo ainda nos esperasse na montanha… O que implica o corpo “entendido enquanto dimensão física/mental/subtil” 6, e a sua localização no espaço, no discurso, na aprendizagem? 7 Caminhar.

Penso na relação entre a recepção da palavra e a localização do corpo no espaço.

Penso em imobilidade e mobilidade. Sinto a cadeira. 8

Location scouting in Arrábida for O Caminho de Nietzsche, 03 March 2012. Photograph: João Wengorovius. Segundo corte: no atelier

Depois dessa defesa de tese, num primeiro encontro no meu atelier, faço à Maria João a proposta de pegarmos no tema nietzschiano A grande saúde, porque com ele vêm as questões da alimentação, da vivência, do espaço, do tempo, da descontinuidade, do corpo, da convalescença, da pausa, da marcha, do intervalo, da liberdade… Começamos então a trabalhar desenrolando este fio. Trabalhar A grande saúde era uma intuição: queria pegar no pensamento de Nietzsche sob um ponto de vista pouco habitual, que escapasse aos mais comuns e possibilitasse pensar ‘o alimento’ num terreno vasto, interesse que já vinha de trabalhos anteriores (Uso da Toalha, projecto iniciado em 2005). A de 4 abril de 2011, a Maria João escreveu-me:

“Envio-te umas palavras de Nietzsche para dar continuação ao nosso projecto: ‘Sou demasiado curioso, demasiado problemático, demasiado atrevido para me contentar com uma resposta grosseira. E Deus é uma resposta grosseira, uma indelicadeza para connosco, pensadores. No fundo, até é simplesmente uma grosseira proibição que se nos impõe: não deveis pensar!… De maneira bem diferente me interessa uma outra questão, da qual depende, mais do que de qualquer curiosidade teológica, a ‘salvação da humanidade’: a questão da nutrição. Para uso diário, podemos formulá-la assim: Como te hás-de alimentar, precisamente no teu caso, para chegares ao máximo de energia, de virtù ao estilo renascentista, de virtude isenta de moralina?’ Para as ‘considerações nutricionais’ de Nietzsche, sugiro-te que leias as primeiras páginas do capítulo Por que sou tão perspicaz do Ecce Homo. Uma achega: para beber, água, nada de álcool, e chá só de manhã.”

Para as “considerações nutricionais” de Nietzsche, sugiro-te que leias as primeiras páginas do capítulo “Por que sou tão perspicaz” do Ecce Homo. Uma achega: para beber, água, nada de álcool, e chá só de manhã.” (4 abril 2011).

Terceiro corte: a exposição e a serra

A pouco e pouco, o conceito da exposição A grande Saúde foi-se definindo: a exposição seria constituída com uma parte ‘dentro’ do espaço (Sala do cinzeiro, Fundação EDP) e a montanha : a parede rebatida do museu de que falo no início do texto. Assim, com a fluidez entre o museu e a serra, entre o dentro e o fora, surgiramu o filme O caminho de Nietzsche (dezasseis vozes), que traria o percurso e o texto para dentro do espaço, e o mapa O caminho Nietzsche, que levaria para fora, para a montanha, a obra.

“Não pertencemos àqueles que só entre livros e impelidos por eles chegam a ter pensamentos — o nosso costume é pensar ao ar livre, andando, saltando, subindo, dançando, de preferência por montes solitários ou junto ao mar, onde até os próprios caminhos se tornam pensativos. As nossas primeiras perguntas quanto ao valor de um livro, de uma pessoa ou de uma música são as seguintes: ‘Sabe ele andar? Ou melhor, sabe ele dançar?…” 9

Comecei a passar temporadas, intercaladas por visitas da Maria João, perto da serra da Arrábida 10, perto da terra, para poder iniciar a ligação entre os alimentos e os primeiros desenhos (porque foi pelo alimento que comecei a série de desenhos); e iniciei as caminhadas na serra para procurar que lugares e que perspectivas queria tomar para a realização do filme O Caminho de Nietzsche – dezasseis vozes, assim como os percursos de reconhecimento para “desenhar” o caminho onde se daria a acção com a leitura, na serra, dos dezasseis textos. A serra é uma reserva natural com áreas protegidas e não foi fácil encontrar um caminho autorizado. Queria descobrir o trajecto e uma forma de o levar para dentro da exposição. Há muito que a ideia de movimento estava no meu trabalho. O passo. Caminhar. E assim surgiu a projecção do mapa: como num mapa de viagem, agradava-me a ideia de despoletar um caminho, um acontecimento, mas de seguida poder guarda-lo sem que nenhum registo físico ficasse na montanha. Agradava-me também que este ‘desenho’ efémero, pelo facto de passar a existir um mapa, pudesse ser sempre, ao longo dos tempos, re-feito. Utopia?

Inventar sobre a terra conhecida — a cartografia do mundo está finalizada – desenhemos por cima. Assim, inspirado na ideia de caminhar e de ligar esse caminhar ao pensamento, desenhou-se um percurso na serra pontuado por dezasseis leituras de textos escolhidos de Nietzsche, e editou-se um mapa com os textos e as instruções.

O mapa também pode ser visto como ‘corte’ ou desvio no espaço e no tempo um desenhar sobrevoando o terreno e o tempo — tanto passado, como presente, como futuro. Corte ou ligação, o passo e o texto entre a terra e o céu. Se a terra traz o caminho, o movimento do corpo traz o pensamento: acção des-contínua – suspensão – tempo.

As instruções inscritas no mapa:

“O Caminho de Nietzsche (Serra da Arrábida)

Pelos tempos fora, em qualquer dia que faça sentido, tire o mapa do envelope e percorra o caminho em metros e em textos. Deverá ler os dezasseis textos na ida e nenhum no regresso. Querendo fazer a ação O Caminho de Nietzsche, pernoite perto do deste caminho e faça-o ao nascer da aurora. São necessárias dezasseis vozes. Na véspera distribua os dezasseis textos pelas dezasseis pessoas.”As instruções estão ‘desenhadas’ para que haja futuro. Mas pode ser uma utopia, pois como tomar conta do infinito que as obras performativas contêm? Basta provocá-lo deixando para isso instruções, documentos, filme? Fotografias? Vozes gravadas?

Começou a tornar-se mais claro que a acção O caminho de Nietzsche pedia um afastamento maior e um contexto concreto. Assim, surgiu a ideia de pernoitar no convento da Arrábida. Estar um tempo no convento também alteraria a forma como se ‘vê’ / ou como se “vive” uma obra. Isto é, quando se ‘vê’ uma exposição ou uma performance num museu ou galeria há um tempo certo para ‘ver’; na acção o Caminho de Nietzsche foi possível aliar e fazer dialogar o tempo para ensair e actuar, com o tempo para viver (dormir, acordar, alimentar – descobrir onde ali nasce ou se põe o sol; a apropriação do lugar). Aquilo que é comum na vivência de um lugar como contexto para criação do ‘menos comum’ – a arte?

Quarto ‘corte’: a propósito das vozes – filme e caminho

O que é ensaiar? Qualquer pessoa pode tirar partido desta experiência: ensaiar, neste caso experimentar dar voz a um pensamento, a um texto. E podemos ver o ensaio aqui de novo como ‘cortar’, sair de nós próprios, sair de um quotidiano. Mais ainda, integrar este gesto criativo num quotidiano. De novo fazer entrar o ar? Fazer entrar o infinito? Todos deveríamos ter espaço para o ensaio, o ensaio de um-eu, um ensaio de um – nós; experimentar a nossa voz, conhecê-la (voz/quotidiano/voz/ensaio). A presença da voz como o que está ‘entre’ dentro do corpo — a voz como o que traz para fora e dá uma forma de uma enorme presença com a sua qualidade presencial e efémera — quando acabamos de dizer já dissemos. A voz é o que mais transporta a nossa identidade, o mistério de sermos únicos. Escolhi então as dezasseis vozes para o filme.

Algumas dessas vozes seriam as mesmas que fariam a leitura de textos na performance na serra. Tinham aberto as inscrições para a acção O caminho de Nietzsche e começava-se a desenhar o grupo (Junho 2012).

Rehearsal-recording with Vasco Pimentel for the 16 voices in the film O Caminho de Nietzsche. Quinto corte: O Caminho de Nietzsche, serra da Arrábida, 5 de Agosto 2012

Sabíamos o percurso: na repérage tínhamos decidido até onde iríamos, tínhamos descoberto uma clareira onde chegar.

“No dia a seguir acordámos cedo para tomar um café rápido e umas sandes de pepino em quadradinhos. Não podíamos perder a aurora e iniciámos a caminhada. Alguém pergunta: ‘estamos todos?’ e a Marta responde: ‘Todos? Todos é uma utopia.” 11

Saímos do convento por volta das 6h30m. E continuámos, de certa forma, o ensaio. A única coisa ‘coreografada’ era a escolha do caminho e a decisão de que os textos eram lidos durante a ida e nenhum na volta. Tinha-se decidido na véspera quais as dezasseis vozes que leriam os textos durante o caminho (algumas eram as das mesmas pessoas que gravaram o texto para o filme). Fomos subindo lentamente a montanha e fazendo as dezasseis paragens, dizendo as dezasseis leituras, ouvindo as dezasseis vozes.

Quando chegámos à clareira final, apercebi-me de que não tinha pensado como ‘saiarímos’ dali, isto é, qual o tempo de permanência no lugar, qual o tempo de silêncio e qual o sinal para ‘desfazer’ a obra.

E foi então que, olhando para cada pessoa, tive uma epifania: vi cada um dos participantes como uma ‘escultura viva’. E percebi que essa era a ‘obra’. E que ela acabara de acontecer.

05 August 2012, Serra da Arrábida. Photograph: Pierre Guibert.

05 August 2012, Serra da Arrábida. Photograph: Pierre Guibert.

1 Texto de Chris Marker para o filme As estátuas também morrem, Alain Resnais e Chris Marker, 1953.

2 Verso de Alexandre O’Neill.

3 Objectos de Errância, obras que elaborei para a dissertação de mestrado O evento como pintura. Mestrado Artes Visuais e Intermédia, Universidade de Évora, 2007.

4 Michel Foucault, Nietzsche, la généalogie, l’histoire, 1971.

5 Nietzsche, Ecce Homo, 1888

6 Alberto Carneiro, texto O subtil na criação: o método não método: “Corpo entendido na sua unidade/identidade/diversidade, enquanto dimensão física/mental/subtil, pela qual o que se torna consciente vai formando um conjunto de relações emergentes de sensações onde todos os órgãos sensoriais se conjugam na construção de imagens plásticas”.

7 Uma imagem acompanha este meu pensamento: uma aula de Joseph Albers (Josef Albers teaching at Yale by John Cohen, ca. 1955): ele está de pé e percorre o espaço ensinando com um círculo na mão. Os alunos estão de roda, também de pé e andam no espaço para onde este os dirige, ouvem-no, e a aula dá-se numa espécie de movimento contínuo. Para Albers, o objetivo das suas aulas era ensinar a ‘ver melhor, ensinar a ‘abrir os olhos’. Acreditava na ligação da observação directa e na descoberta pessoal.

8 E outra imagem vem-me ao pensamento: vestígios de experiências pedagógicas do Jardins de Infância (de 1966 a 1975) projectados e dirigidos pela minha mãe. O espaço, uma casa enorme com um jardim muito grande, uma casa como que abandonada, vazia, onde a escola ocupava um espaço emprestado e um pouco de terreno onde plantávamos. A imagem, para além de outras, que importa aqui agora somos nós, alunos, crianças, sentados no chão, numa roda, no centro está um aquário com um peixe, vamos observando o seu movimento, estamos a “estudar” o peixe. Primeiro eram-nos apresentadas ‘as coisas”, a realidade (observação); depois vinha a descrição verbal dos conhecimentos que adquiríamos da observação (associação) e por fim o desenho ou as palavras escritas (expressão). Assim apareciam no meio do espaço da aula galinhas, coelhos, peixes… por vezes improvisavam-se redes para manter o animal dentro da sala e muitas vezes, depois da acção, estes ficavam a viver na escola. Este método advinha das experiências pedagógicas propostas por Decroly, que seguem do concreto para o abstracto, através aquilo a que Decroly chamava os centros de interesse. Este desenvolveu uma pedagogia que fazia uso da globalização por acreditar tratar-se de um caminho natural para apreender o conhecimento. O seu método questionou a divisão das disciplinas pois considerava que isso não permitia o conhecimento da realidade viva (total).Dizia que o ensino fragmentado não favorecia o desenvolvimento da inteligência, porque reduzia a aprendizagem a uma transmissão isolada, o que por vezes podia até levar a criança a desinteressar-se pela escola. Penso hoje o quanto é importante revesitar estes assuntos.

9 Texto N1 do Mapa O Caminho de Nietzsche (textos escolhidos pela Maria João para o projecto do caminho).

10 Elaboração dos desenhos que constituiriam a exposição sobre o tema a Grande Saúde, Fundação EDP, onde também seria exposto o mapa: O Caminho de Nietzsche e o filme O Caminho de Nietzsche – dezasseis vozes, 2012.

11 Tirado do texto “Relato sobre evento no Convento da Arrábida (parte 1)”, Maria Lusitano Santos. - + EN

-

Inside Outside Between

O Caminho de Nietzsche, Serra da Arrábida, 2012

Marta Wengorovius (April 2014)“When men die, they enter history. When statues die, they enter art. This botany of death is what we call culture.” 1

“The infinite?/ Tell him to come in./ It’s good for infinity/ to be among human company.” 2

Prologue

A work of art, like philosophy, should stir up currents of air. It should inspire us, bring in the infinite.

Since 2005, I’ve discovered, in myself and in my work, a predisposition towards, or even a fascination with, the transposition of a museum’s walls into the street, into the city and into nature. Sometimes, as in the case of Objectos de Errância (2005-2012) 3, this signifies the possibility of taking the works outside – using them and then returning them to be kept in their boxes or in the museum. From 2005 to 2012, these Objectos de Errância were ‘used’ for staged encounters. These encounters were more complex or less complex depending on each situation. For example: when I was invited to participate in an exhibition at the Centro Cultural de Cascais, organised by Quinta Essência (an association that works with autistic people), I found myself in a garden with a teenager from the association, who was to make use of two works that I had just finished creating: Olho #1 and Olho #2 (arco-íris). The exhibition was that very moment that took place in the garden – the use of the objects, the time allotted for the exhibition – and the garden was the museum. Some of the more complex performances of Objectos de errância required me to study locations, produce drawings and draw up action plans, or figure out when the sunset or sunrise would occur on specific days. Some events took place in the mountains, others at a beach, outside or inside the museum. The image of a museum’s walls transposed to some other place also signifies a possible connection with the city, with the university, with the garden – a communication that opens the museum’s ‘architecture-box’ or closes it, depending on the requirements of the work. In the museum, the works of art become works that open to the other, to the unknown; in the case of Objectos de errância, where they might be requisitioned for use, this is an important factor. Inside, outside, between: the museum and the everyday as spaces in fluid dialogue, making the most of their potentialities. Perhaps “statues need not die” there. Is this utopian?

Michel Foucault wrote:

“History becomes “effective” to the degree that it introduces discontinuity into our very being – as it divides our emotions, dramatizes our instincts, multiplies our body and sets it against itself. […] Knowledge is not made for understanding; it is made for cutting.” 4First cut: University

We are at the Faculty of Social and Human Sciences at Universidade Nova de Lisboa on 2 December 2010. Inside the university’s small auditorium, a PhD thesis on Nietzsche is being defended. The title of the thesis is Art and Philosophy in Nietzsche’s Thinking and the candidate is Maria João Mayer Branco. While I listen attentively and take in all of her words, an idea stirs in me (or does it stir me up?): what would this text be like if it were read in another context? How would one transpose this discourse onto a mountain? How would it be turned into an experience? I think about what knowledge is – what does it mean to understand? – to inspire, to bring in the infinite. I think about how one might visit and enter other people’s thoughts. How one enters and exits. What it brings. And how what stays with us sometimes ends up staying for good. A phrase, a thought, an idea.

“Remain seated as little as possible, put no trust in any thought that is not born in the open, to the accompaniment of free bodily motion – nor in one in which even the muscles do not celebrate a feast. All prejudices take their origin in the intestines. A sedentary life, as I have already said elsewhere, is the real sin against the Holy Spirit.” 5

If, as Nietzsche asserts, the best thoughts emerge outdoors and while one is walking, should we not heed this advice? What would happen if the reception of a thought meant changing the location in which we found ourselves – as if the philosopher were still waiting for us on the mountain… What would it mean to have the body “understood as a physical/mental/subtle dimension” 6 , and to be located in space, in discourse, in learning? 7 In a word: walking.

I think of the relationship between the reception of a word and the location of a body in a space.

I think of immobility and mobility. I feel the chair. 8

Location scouting in Arrábida for O Caminho de Nietzsche, 03 March 2012. Photograph: João Wengorovius. Second cut: in the studio

After the thesis defence, I had my first meeting with Maria João in my studio, where I suggested to her the idea of adopting Nietzsche’s The Great Health, since it brought up questions of diet, existence, space, time, discontinuity, the body, convalescence, pausing, walking, the interval, freedom…

We thus set to work to unravel this thread. Working on The Great Health was something intuitive: I wanted to use Nietzsche’s thinking from an unusual perspective that escaped most people’s awareness, allowing one to think of ‘food’ within a vast terrain, an interest of mine that had already been present in previous work (Uso da Toalha [Use of the Tablecloth], a project that began in 2005). On 4 April 2011, Maria João wrote to me:

“I’m sending you some words by Nietzsche to continue further with our project: ‘I’m too inquisitive, too incredulous, too high spirited, to be satisfied with such a palpably clumsy solution of things. God is a too palpably clumsy solution of things; a solution which shows a lack of delicacy towards us thinkers – at bottom, He is really no more than a coarse and rude prohibition of us: ye shall not think!… I am much more interested in another question: a question upon which the ‘salvation of humanity’ depends to a far greater degree than it does upon any piece of theological curiosity: I refer to nutrition. For ordinary purposes, it may be formulated as follows: how precisely must though feed thyself in order to attain to thy maximum of power, or virtù in the Renaissance style, of virtue free from moralic acid?’9 On Nietzsche’s “nutritional considerations”, I suggest you read the opening pages of the chapter “Why I am so Clever” in Ecce Homo. Another thing: drink water, no alcohol. And tea only in the morning.” (4 April 2011).

Third cut: the exhibition and the hills

Bit by bit, the concept of the exhibition A grande Saúde was defined: the exhibition would be comprised of a part that was ‘inside’ a space (Sala do cinzeiro, Fundação EDP) and one that was on in the hills: the transposed wall of the museum that I mentioned at the beginning of this text. What emerged, then, in the fluidity between museum and mountain, between inside and outside, was the film O caminho de Nietzsche (dezasseis vozes) [Nietzsche’s Way (16 voices)], which would bring the trail and the text into the space, and a map, O caminho Nietzsche, which would take the work outside to the hills.

“We are not among those who have ideas only between books, stimulated by books – our habit is to think outdoors, walking, jumping, climbing, dancing, preferably on lonely mountains or right by the sea where even the paths become thoughtful. Our first question about the value of a book, a person, or a piece of music is: ‘Can they walk?’ Even more, ‘Can they dance?’” 10

I began to spend time near the Serra da Arrábida , close to the land, interspersed with visits from Maria João, so I could begin making a link between food and the first drawings (it was through food that I began the series of drawings). I also began to take walks in the hills to find the locations and perspectives I wanted for the film O Caminho de Nietzsche – dezasseis vozes, and to scout for the routes that would “draw” the trail, where the activity and the readings of the 16 texts would take place. The serra is in a nature reserve with protected areas and it was not easy to find an authorised trail. I wanted to find a path and a way to bring it into the exhibition. The idea of movement had been in my work for quite some time. The step. And walking. This is how the projection of the map emerged: as in a travel map, I liked the idea of blazing a trail, creating an event, but one that could later be recorded without leaving any physical trace on the mountain. What I also liked was that this ephemeral ‘drawing’, the fact that it existed on a map, could always be redone over time. Is this utopian? To invent atop a land that is familiar – the world having already been mapped – we draw over it. Inspired by the idea of walking and of connecting the walking with thinking, a trail was created in the hills, marked by 16 readings of selected texts by Nietzsche, and a map was produced, containing texts and instructions. The map can also be regarded as a ‘cut’ or a diversion in space and time, a drawing that floats above the land and time – as much in the past as it is in the present and the future. A cutting or a connection, a step and a text between the land and the sky. If the land provides the trail, the movement of the body provides the thought: dis-continuous action – suspension – time.

The written instructions on the map:

“O Caminho de Nietzsche (Serra da Arrábida). At any time, on any day that seems appropriate, remove the map from the envelope and follow the trail by metres and texts. You should read the 16 texts on the way there; do not read any of them on the way back. If you want to perform O Caminho de Nietzsche, spend the night somewhere close to the trail and set out at dawn. You need 16 voices. On the evening before you set out, distribute the 16 texts to 16 people.” 11

The instructions are ‘drawn’ so as to have a future. Perhaps this is utopian, for how does one grasp the infinite that exists in performative works? Is it enough to instigate it by leaving instructions, documents, a film? Photographs? Recorded voices? It became clear that the performance of O caminho de Nietzsche required greater seclusion and a concrete context. Out of this came the idea of spending a night at the Arrábida Convent. Spending time in the convent would also change how one ‘saw’ or ‘experienced’ a work of art. In other words, when one sees an exhibition or watches a performance at a museum or gallery, there is a specific time allotted for ‘viewing’; on Nietzsche’s Way, one could combine the time spent on rehearsing and performing with the time spent on living (sleeping, waking up, eating – discovering where the sun rises and sets; getting acquainted with the place) and create a dialogue between them. To take what is ordinary in the experience of a place as a context for creating something ‘not so ordinary’ – could that be art?

Fourth ‘cut’: about the voices – the film and the trail

What does it mean to rehearse? Anyone can benefit from this experience: to rehearse, in this case, is to try to give voice to a thought, to a text. Once again, we might view the rehearsal here as a ‘cut’, to step out of ourselves, to remove ourselves from the everyday. And more: to include this creative gesture in the everyday. Perhaps it’s to inspire, to bring in the air? To bring in the infinite? All of us should have a space to rehearse in, a rehearsal for the ‘I’, a rehearsal for the ‘We’; to experiment with our voice and to get to know it (voice/everyday/voice/rehearsal). The presence of the voice as something that is ‘in between’, inside the body – the voice as something that is transposed to the outside and gives shape to an enormous presence with its ephemeral and present quality – when we have just finished saying something, when we have already said it. The voice is what best transports our identity, the mystery of our uniqueness. I then proceeded to select the 16 voices for the film.

Some of these voices would be the same voices that would read the texts in the performance in the hills. I held auditions for the performance of O caminho de Nietzsche and began to assemble the group (June 2012).

Rehearsal-recording with Vasco Pimentel for the 16 voices in the film O Caminho de Nietzsche. Fifth cut: O caminho de Nietzsche, Serra da Arrábida, 5 August 2012

We knew the route: during the location scouting, we had decided where we would walk and we had found a clearing where we would end up.

“The next day, we woke up early and ate a quick breakfast and several cucumber sandwiches that had been cut up into squares. We couldn’t miss the sunrise so we began the walk. Someone asked: ‘is everyone here?’ and Marta replied: ‘Everyone? Everyone would be a utopia.” 12

We left the convent around 6:30 AM, continuing the rehearsal, in a sense. The only thing that was ‘choreographed’ was the path that had been selected and the decision to read the texts on the way up and not to read any on the way back. It had been decided the night before which of the 16 voices would read the texts along the trail (some were the same people who recorded the readings for the film). Slowly, we ascended the mountain, stopping in 16 places, performing the 16 readings and listening to the 16 voices. When we arrived at the final clearing, it occurred to me that I had not given any thought as to how we would ‘leave’ the place; that is, how long we would stay there, how long the silence would go on for and what the signal would be for ‘ending’ the work.

It was at that moment, as I looked at each person, that I had an epiphany: I saw each participant as a ‘living sculpture’. And I realised that this was the ‘work’. And that it had just happened.

05 August 2012, Serra da Arrábida. Photograph: Pierre Guibert.

05 August 2012, Serra da Arrábida. Photograph: Pierre Guibert.

1 Text from the film Statues Also Die (Les Statues Meurent Aussi), Alain Resnais and Chris Marker, 1953. Retrieved from: http://www.walkerart.org/calendar/2014/censorship-colonial-france-returning-gaze

2 Poem by Alexandre O’Neill [transl. Richard Zenith, 1997], Poetry International Rotterdam. Retrieved from: http://www.poetryinternationalweb.net/pi/site/poem/item/4720/auto/PORTUGAL

3 Objectos de Errância were works created for my Master’s dissertation entitled O evento como pintura. Master’s in Visual Arts and Intermedia, Universidade de Évora, 2007.

4 Michel Foucault, Nietzsche, genealogy, history, pp. 124 in The Postmodern History Reader, ed. Keith Jenkins, Routledge, London and New York, 1997.

5 Nietzsche, Ecce Homo, 1888 [translated by Anthony M. Ludovici, 1911]

6 Alberto Carneiro, text from O subtil na criação: o método não método: “The body is understood in its unity/identity/diversity as a physical/mental/subtle dimension, so that what becomes conscious forms a series of emerging relations of sensations in which all of the sensorial organs come together to build artistic images” (direct translation from the Portuguese version).

7 An image accompanies this thought: a lesson taught by Joseph Albers (Josef Albers teaching at Yale by John Cohen, ca. 1955): he is standing and he walks around the space as he teaches, holding a circle in his hand. The students stand around him in a circle and they walk in the space where he tells them to walk; they listen to him and the class becomes a kind of continuous movement. For Albers, the goal of his lessons was to teach people how to ‘see better’, to teach them to ‘open their eyes’. He believed in the connection between direct observation and personal discovery.

8 Another image comes to mind: memories of pedagogical experiments in kindergarten (from 1966 to 1975), conceived and directed by my mother. The space was an enormous house with a very large garden, a house that was sort of abandoned, empty, where the school was using a borrowed space and a small plot where we planted things. Among other images, the one that is important here is of us – students, children – sitting on the floor in a circle. In the middle is an aquarium with a fish; we’re observing its movements, we’re “studying” the fish. First, we were presented with ‘things’, reality (observation); later came a verbal description of the knowledge we would acquire from observation (association) and finally, a drawing or written words (expression). Chickens, rabbits and fish would appear in the middle of the classroom space… sometimes improvised wire netting was created to keep the animals inside the room and often, they would end up living in the school. This method was based on Decroly’s pedagogical experiments, which proceeded from the concrete to the abstract through what he called centres of interest. He developed a pedagogy that employed the idea of globalisation, as he believed it was a natural path for attaining knowledge. His method questioned the separation of the disciplines, as he thought that this would not allow for an understanding of lived reality (totality). He argued that a fragmented education did not encourage the development of intelligence, since it reduced learning to an isolated transmission, one that could even lead a child to lose interest in school. I think it is so important nowadays to revisit these issues.

9 Friedrich Nietzsche, Ecce Homo, [transl. Anthony M. Ludovici], p. 29, Dover, New York, 2004

10 Friedrich Nietzsche, The gay science: with a prelude in German rhymes and an appendix of songs, [transl. Josefine Nauckhoff], p. 230, Cambridge University Press, NY, 2001, Text N1 from the Map O Caminho de Nietzsche (texts selected by Maria João for the trail).

11 Preparing the drawings that would comprise the exhibition based on the theme The Great Health, Fundação EDP, where mapa: O Caminho de Nietzsche and the film O Caminho de Nietzsche – dezasseis vozes, 2012 would also be presented.

12 Excerpted from the text “Relato sobre evento no Convento da Arrábida (parte 1)”, Maria Lusitano Santos.